DPR

Dissociated Pain Release

A self-help technique developed by a trauma survivor

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach

Master's Clinical Psychology - Harvard University

Dissociated Pain Release

Self-Help Trauma Support

Dissociated Pain Release

Dissociated Pain Release (DPR) is a self-help technique that allows users to release emotional pain from trauma without re-experiencing it. It is based on the idea that emotional pain is stored in the mind, body, and nervous system and that the stored pain causes distress and discomfort in the present, whether the trauma was a recent event or something that happened many years ago.

There is no need for a DPR user to know where any emotional pain came from. All a user needs to know is that they are currently experiencing unwanted emotional pain and that they would like to release that pain and feel better -- quickly.

Most importantly, in DPR, emotional pains are released while the user is dissociated from them -- allowing the user to process any trauma or distress without being forced to relive the original traumatic experience.

Examples of emotional pain that can be released from the body and nervous system through DPR include rage, anger, shame, sadness, guilt, grief, loneliness, abandonment, anxiety, and fear.

Likewise, DRP allows users to release any stored sensations associated with physical pain or forms of bodily discomfort that happened in the past. DPR users can release sensations of nausea, dizziness, cold, being drugged, etc. Again, all these sensations are released without the DRP user re-experiencing the original potency of any traumatic event. Often DPR users release pain without even knowing what the original traumatic event may have been.

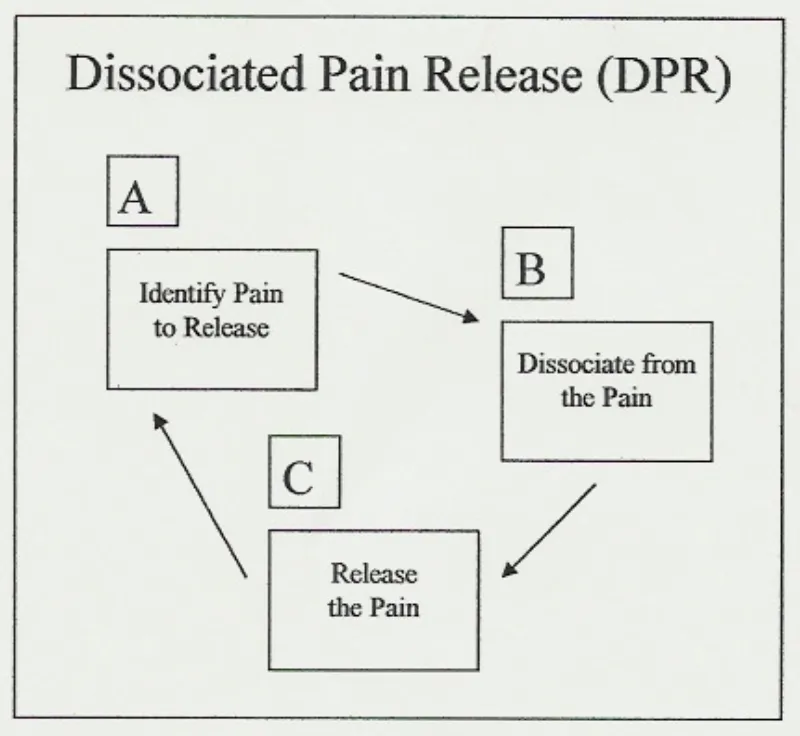

DPR has three cyclical steps: (A) identify pain to release, (B) dissociate from the pain, and (C) release the pain. Once understood, DPR is a simple, repetitive process that applies in many self-help situations. Any user employing DPR expects to complete its A-B-C cycle several times in any one self-help session. It is understood that there may be several painful emotions, different forms of physical pain and other negative bodily sensations that require release, making time and repetition necessary.

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not. It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach, Educator

Master's Clinical Psychology, Harvard Univerisity

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not.

It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline:

https://findahelpline.com/

About Me

Like many others, I grew up in a household that didn't offer me the basic protections all children need. I experienced extreme trauma as a very young child and, unfortunately, that trauma continued into my adolescence and adulthood.

I survived adolescence emotionally by focusing on studying contemporary dance, helping me process my emotions and increase my body awareness. As a young adult in my twenties, I was exposed to relaxation and meditation techniques and the idea that healing that comes naturally when we move our eyes as we dream.

In my mid-twenties, memories of traumatic events that had happened during my early childhood began to return to my consciousness. I knew about EMDR (Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy for trauma, but wasn't in a situation that allowed me consistent access to a trauma therapist.

So, I began working through my traumatic memories on my own, combining what I'd learned about the emotions I felt in my body through dancing with relaxation and visualization techniques. I added what I decided to call REM Simulation -- or Rapid Eye Movement Simulation. REM sleep is the deep dreaming sleep in which humans naturally process emotions.

The result was a self-help technique that made it possible for me to work through the terrible emotions associated with traumatic events that had occurred in my past and regain the sense of emotional stability I needed -- all without having an opportunity to get the therapeutic support I needed.

Dissociated Pain Release

I dubbed my self-help technique DPR, or Dissociated Pain Release, and decided that I didn't want it to ever become something that anyone with an advanced degree and a lot of privilege could tell people they weren't qualified to perform at home on their own.

Therapy is wonderful and everyone who has access to a therapist should take advantage of that privilege. But recovery strategies should be available to anyone anywhere. That's what DPR is about for me.

From my perspective, DPR is nothing more than a collection of practical ideas put together in one package to help all of us get through the difficult emotions humans feel. It's valuable because it works and it uses human's natural REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep processing methods.

My Newest Blog Posts

Neurodiverse Families and the Co-Occurrence of Autism and Attention Neurodivergence (ADHD): Insights from Recent Studies

Neurodiverse families often include various types of neurodivergence beyond autism. A significant 2017 study conducted by Ghirardi et al. sheds light on a crucial finding: autism (AS-ND) and attention neurodivergence (A-ND or ADHD) frequently co-occur within the same families. The study, which examined nearly 1.9 million individuals born in Sweden between 1987 and 2006, demonstrated that relatives of individuals with autism are more likely to have attention neurodivergence than individuals without such familial connections. This suggests a strong familial link between autism and attention neurodivergence, further reinforcing the understanding that neurodivergent variations often cluster within the same families.

One of the key takeaways from this research is that many autistic individuals are also diagnosed with ADHD. Despite this, it wasn't until 2013 that the American Psychiatric Association officially recognized the possibility of these two conditions co-occurring, allowing for dual diagnoses. Before this change, autistic individuals presenting with attention neurodiverence were often left with one diagnosis or the other, leaving gaps in their treatment and understanding of their neurological differences.

The 2017 study by Ghirardi et al. provided more than just clinical observations of co-aggregation; it inspired further research into the potential genetic links between autism and attention neurodivergence. This search led to a groundbreaking discovery in 2021 when Suk-ling Ma et al. identified a gene, SHANK2, that may play a key role in the overlap between these two neurodivergences. SHANK2 is thought to be a potential genetic marker underlying the co-occurrence of autism and attention neurodivergence within the same families.

The findings from these studies offer essential insights into the genetic and clinical dynamics of neurodiverse families. Not only do they demonstrate that autism and attention neurodivergence frequently co-occur, but they also highlight that while many autistic individuals may are also attention neurodivergents, this is not universally the case. The identification of SHANK2 as a potential genetic link opens new avenues for further research into the biological underpinnings of these neurodivergent variations.

Understanding the familial and genetic overlaps between autism and attention neurodivergence can help inform more personalized approaches to diagnosis and treatment, ensuring that individuals and families receive appropriate support for their unique neurodivergent profiles. As research continues to evolve, it is clear that the co-occurrence of different neurodivergences, such as autism and attention neurodivergence, is an important aspect of understanding neurodiverse family systems. By exploring these connections, we can better support individuals and families navigating the complexities of neurodivergence.

Ultimately, these studies serve as a reminder that neurodiversity is multifaceted, and families often face overlapping challenges that extend beyond a single neurological variation. The recognition and understanding of co-occurring neurodivergent qualities provide a foundation for more inclusive research, education, and interventions that reflect the true diversity of human neurology [2.1].

Resources for Further Exploration:

Read Ghirardi et al.'s 2017 study "The Familial Co-Aggregation of ASD and ADHD: A Register-Based Cohort Study" published by the Journal of Molecular Psychiatry, Feb. 2018 23(2), 257-262, doi:10.1038/mp.2017.17. Other authors: I. Brikell, R. Kuja-Halkola, C.M. Freitag, B.Franke, P. Asherson, P. Lichtenstein, and H. Larsson.

Read Suk-Ling Ma et al.'s 2021 research "Genetic Overlap Between Attention Defecit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in SHANK2 Gene" published by Fronteirs in Neuroscience, Vol. 15, doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.649588. Other authors: Lu Hua Chen, Chi-Chiu Lee, Kelly Y. C. Lai, Se-Fong Hung, Chun-Pan Tang, Ting-Pong Ho, Caroline Shea, Flora Mo, Timothy S.H. Mak, Pak-Chung Sham, and Patrick W. L. Leung.</text>

Learn more about the SHANK2 gene.

© 2023 REAL Neurodiverse

All Rights Reserved

anne@neurodiversemarriage.com

Text or Call: (617) 996-7239 (United States)