DPR

Dissociated Pain Release

A self-help technique developed by a trauma survivor

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach

Master's Clinical Psychology - Harvard University

Dissociated Pain Release

Self-Help Trauma Support

Dissociated Pain Release

Dissociated Pain Release (DPR) is a self-help technique that allows users to release emotional pain from trauma without re-experiencing it. It is based on the idea that emotional pain is stored in the mind, body, and nervous system and that the stored pain causes distress and discomfort in the present, whether the trauma was a recent event or something that happened many years ago.

There is no need for a DPR user to know where any emotional pain came from. All a user needs to know is that they are currently experiencing unwanted emotional pain and that they would like to release that pain and feel better -- quickly.

Most importantly, in DPR, emotional pains are released while the user is dissociated from them -- allowing the user to process any trauma or distress without being forced to relive the original traumatic experience.

Examples of emotional pain that can be released from the body and nervous system through DPR include rage, anger, shame, sadness, guilt, grief, loneliness, abandonment, anxiety, and fear.

Likewise, DRP allows users to release any stored sensations associated with physical pain or forms of bodily discomfort that happened in the past. DPR users can release sensations of nausea, dizziness, cold, being drugged, etc. Again, all these sensations are released without the DRP user re-experiencing the original potency of any traumatic event. Often DPR users release pain without even knowing what the original traumatic event may have been.

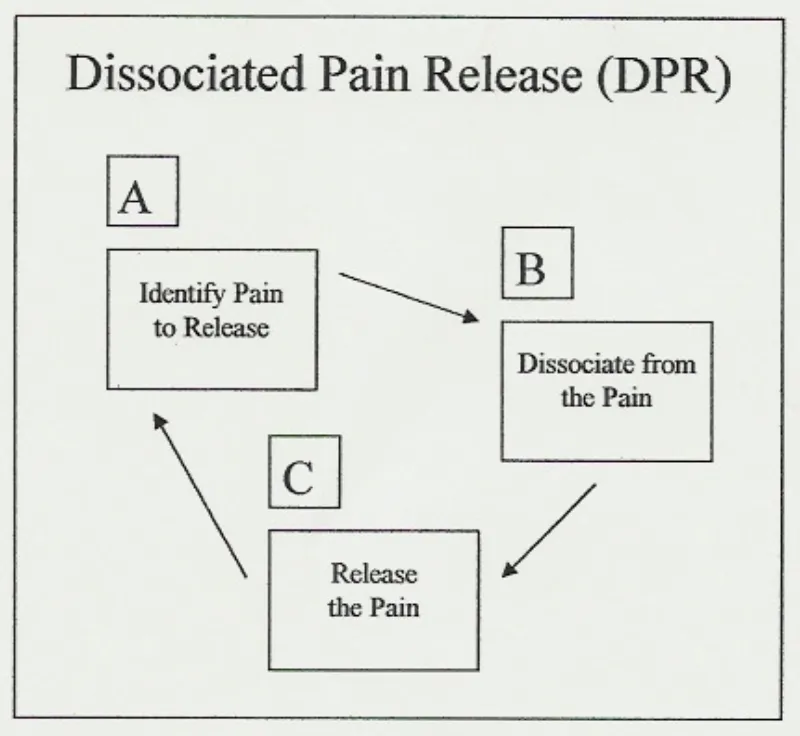

DPR has three cyclical steps: (A) identify pain to release, (B) dissociate from the pain, and (C) release the pain. Once understood, DPR is a simple, repetitive process that applies in many self-help situations. Any user employing DPR expects to complete its A-B-C cycle several times in any one self-help session. It is understood that there may be several painful emotions, different forms of physical pain and other negative bodily sensations that require release, making time and repetition necessary.

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not. It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach, Educator

Master's Clinical Psychology, Harvard Univerisity

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not.

It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline:

https://findahelpline.com/

About Me

Like many others, I grew up in a household that didn't offer me the basic protections all children need. I experienced extreme trauma as a very young child and, unfortunately, that trauma continued into my adolescence and adulthood.

I survived adolescence emotionally by focusing on studying contemporary dance, helping me process my emotions and increase my body awareness. As a young adult in my twenties, I was exposed to relaxation and meditation techniques and the idea that healing that comes naturally when we move our eyes as we dream.

In my mid-twenties, memories of traumatic events that had happened during my early childhood began to return to my consciousness. I knew about EMDR (Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy for trauma, but wasn't in a situation that allowed me consistent access to a trauma therapist.

So, I began working through my traumatic memories on my own, combining what I'd learned about the emotions I felt in my body through dancing with relaxation and visualization techniques. I added what I decided to call REM Simulation -- or Rapid Eye Movement Simulation. REM sleep is the deep dreaming sleep in which humans naturally process emotions.

The result was a self-help technique that made it possible for me to work through the terrible emotions associated with traumatic events that had occurred in my past and regain the sense of emotional stability I needed -- all without having an opportunity to get the therapeutic support I needed.

Dissociated Pain Release

I dubbed my self-help technique DPR, or Dissociated Pain Release, and decided that I didn't want it to ever become something that anyone with an advanced degree and a lot of privilege could tell people they weren't qualified to perform at home on their own.

Therapy is wonderful and everyone who has access to a therapist should take advantage of that privilege. But recovery strategies should be available to anyone anywhere. That's what DPR is about for me.

From my perspective, DPR is nothing more than a collection of practical ideas put together in one package to help all of us get through the difficult emotions humans feel. It's valuable because it works and it uses human's natural REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep processing methods.

My Newest Blog Posts

Level 1 Autistic Adults in Our Families and Communities: Unseen Challenges and Neurodiverse Communication

Autism is a natural neurological variation that affects communication and socializing. Level 1 autism is characterized by its subtler manifestations. Many trained professionals have difficulties recognizing it in adults due, in part, to the reality that many Level 1 autistic adults have developed effective compensatory strategies, helping them to manage the difficulties they face socializing with non-autistics.

Level 1 autism also requires less support than Levels 2 and 3 autism and professionals tend to prioritize to supporting Level 1 autistic children over Level 1 autistic adults. Level 1 autism is also much more apparent in children and many adults remain undiagnosed leading to a situation in which Level 1 autistic adults are integrated into our families and communities with relatively little societal or professional awareness of their presence or neurological differences.

The Journey from Childhood to Adulthood with Level 1 Autism

Children with Level 1 autism often struggle with social cues, making their condition more noticeable during early development. These children may find it difficult to engage in typical social interactions, leading to challenges in forming friendships and understanding social norms. However, as they grow older, many autistic individuals develop strategies to cope with and mask their social difficulties.

One key strategy is the use of declarative memory—the ability to recall facts and details. Autistic individuals often rely on their declarative memory to memorize social rules and patterns through a process of trial and error. When a particular behavior or response leads to social success, they are likely to repeat it, gradually building a repertoire of socially acceptable behaviors. Over time, this learned behavior can make their autism less apparent, allowing them to blend into the social world more seamlessly.

However, this adaptation does not change the fundamental differences in how their brains process social information. While these individuals may appear socially adept, they often continue to experience significant internal challenges, including anxiety, exhaustion, and confusion, as they work to navigate a world that inherently operates differently from their natural inclinations.

The Underdiagnosis of Level 1 Autism in Adults

A significant number of adults with Level 1 autism were never diagnosed as children, particularly those born before the 21st century when awareness and understanding of autism were far less developed. These individuals grew up in a world that largely did not recognize their neurological differences, leaving them to develop coping mechanisms on their own. As a result, many of these adults have gone "under the radar," living their lives without a formal diagnosis or understanding of their neurological variation.

This lack of recognition is not only a missed opportunity for support but also contributes to ongoing challenges in communication and social interactions. Without the framework of an autism diagnosis, these individuals—and those around them—may not fully understand the source of their social difficulties. This can lead to frustration, misunderstandings, and strained relationships in both personal and professional settings.

The Impact of Neurodiverse Miscommunications

The differences in how autistic and non-autistic brains perceive and process social information can lead to frequent miscommunications. These miscommunications occur across all areas of life—online, offline, in the workplace, and within families. Autistic individuals may struggle to interpret the non-verbal cues, tone of voice, or implied meanings that non-autistic individuals are using to communicate with each other and that they attempt to use to communicate with autistics, not knowing that the autistics aren't interpreting their cues in the same ways the non-autistics mean them. Non-autistic individuals may also misinterpret autistics' differences voice inflection, facial expressions and body language as rudeness or dismissal, while the autistics have no intention to communicate such messages. Autistics' more direct communication style, literal thinking, or unique perspectives can amplify the non-autistic sense that Level 1 autistics are rude, disinterested, or lack understanding.

These misunderstandings are compounded by the fact that most people do not assume that someone else’s brain might work fundamentally differently from their own. Because Level 1 autism is often "invisible" in adults, these individuals may be perceived as quirky, introverted, or socially awkward rather than recognized as neurodivergent. This lack of awareness on both sides can lead to feelings of isolation, frustration, and conflict.

Recognizing and Supporting Neurodiverse Individuals

Given the prevalence of undiagnosed Level 1 autism in adults, it is crucial to foster a greater awareness and understanding of neurodiversity in our communities. Recognizing that not everyone processes social information in the same way is the first step toward reducing the frequency and impact of neurodiverse miscommunications.

For non-autistic individuals, this means being mindful of the different ways people communicate and interact. It involves being patient, asking clarifying questions, and avoiding assumptions about someone’s intentions or abilities based on their social behavior. For autistic individuals, receiving a diagnosis later in life can be a powerful tool for self-understanding and acceptance, as well as for seeking appropriate support and accommodations.

In the workplace, educational settings, and social environments, creating spaces that are inclusive and accommodating of neurodiverse needs can help bridge the communication gap between autistic and non-autistic individuals. This includes providing clear, direct communication, offering written instructions or reminders, and fostering an environment where all communication styles are respected and valued.

Conclusion

Level 1 autism in adults presents unique challenges that often go unrecognized due to the subtleties of the neurological variation. While many individuals have developed sophisticated compensatory strategies to navigate the social world, the fundamental neurological differences between autistic and non-autistic individuals remain. These differences can lead to frequent and sometimes significant miscommunications, affecting relationships and well-being.

By increasing awareness and understanding of Level 1 autism and the diverse ways in which it can manifest, we can create more inclusive and supportive environments for all individuals. Recognizing and respecting neurodiversity not only helps reduce miscommunications but also enriches our communities by valuing the unique perspectives and contributions of every individual.

Support for Professionals and Clients:

Neurodiverse Credentialing and Practice Support for Psychologists, Therapists, Social Workers, Clergy, and Domestic Violence workers is available here.

Autistic and non-autistic members of neurodiverse family systems can reach out for support here.

© 2023 REAL Neurodiverse

All Rights Reserved

anne@neurodiversemarriage.com

Text or Call: (617) 996-7239 (United States)