DPR

Dissociated Pain Release

A self-help technique developed by a trauma survivor

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach

Master's Clinical Psychology - Harvard University

Dissociated Pain Release

Self-Help Trauma Support

Dissociated Pain Release

Dissociated Pain Release (DPR) is a self-help technique that allows users to release emotional pain from trauma without re-experiencing it. It is based on the idea that emotional pain is stored in the mind, body, and nervous system and that the stored pain causes distress and discomfort in the present, whether the trauma was a recent event or something that happened many years ago.

There is no need for a DPR user to know where any emotional pain came from. All a user needs to know is that they are currently experiencing unwanted emotional pain and that they would like to release that pain and feel better -- quickly.

Most importantly, in DPR, emotional pains are released while the user is dissociated from them -- allowing the user to process any trauma or distress without being forced to relive the original traumatic experience.

Examples of emotional pain that can be released from the body and nervous system through DPR include rage, anger, shame, sadness, guilt, grief, loneliness, abandonment, anxiety, and fear.

Likewise, DRP allows users to release any stored sensations associated with physical pain or forms of bodily discomfort that happened in the past. DPR users can release sensations of nausea, dizziness, cold, being drugged, etc. Again, all these sensations are released without the DRP user re-experiencing the original potency of any traumatic event. Often DPR users release pain without even knowing what the original traumatic event may have been.

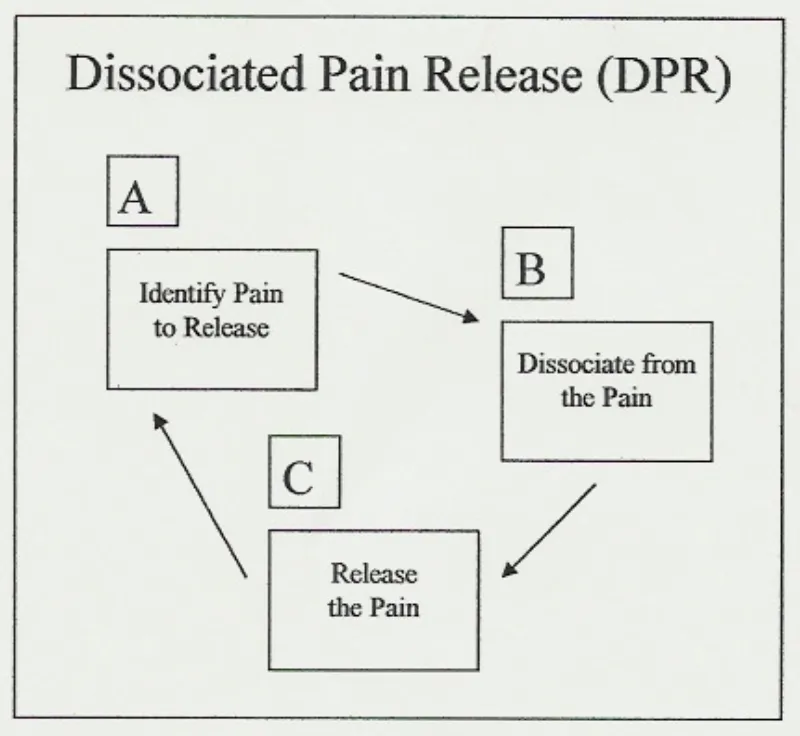

DPR has three cyclical steps: (A) identify pain to release, (B) dissociate from the pain, and (C) release the pain. Once understood, DPR is a simple, repetitive process that applies in many self-help situations. Any user employing DPR expects to complete its A-B-C cycle several times in any one self-help session. It is understood that there may be several painful emotions, different forms of physical pain and other negative bodily sensations that require release, making time and repetition necessary.

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not. It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach, Educator

Master's Clinical Psychology, Harvard Univerisity

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not.

It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline:

https://findahelpline.com/

About Me

Like many others, I grew up in a household that didn't offer me the basic protections all children need. I experienced extreme trauma as a very young child and, unfortunately, that trauma continued into my adolescence and adulthood.

I survived adolescence emotionally by focusing on studying contemporary dance, helping me process my emotions and increase my body awareness. As a young adult in my twenties, I was exposed to relaxation and meditation techniques and the idea that healing that comes naturally when we move our eyes as we dream.

In my mid-twenties, memories of traumatic events that had happened during my early childhood began to return to my consciousness. I knew about EMDR (Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy for trauma, but wasn't in a situation that allowed me consistent access to a trauma therapist.

So, I began working through my traumatic memories on my own, combining what I'd learned about the emotions I felt in my body through dancing with relaxation and visualization techniques. I added what I decided to call REM Simulation -- or Rapid Eye Movement Simulation. REM sleep is the deep dreaming sleep in which humans naturally process emotions.

The result was a self-help technique that made it possible for me to work through the terrible emotions associated with traumatic events that had occurred in my past and regain the sense of emotional stability I needed -- all without having an opportunity to get the therapeutic support I needed.

Dissociated Pain Release

I dubbed my self-help technique DPR, or Dissociated Pain Release, and decided that I didn't want it to ever become something that anyone with an advanced degree and a lot of privilege could tell people they weren't qualified to perform at home on their own.

Therapy is wonderful and everyone who has access to a therapist should take advantage of that privilege. But recovery strategies should be available to anyone anywhere. That's what DPR is about for me.

From my perspective, DPR is nothing more than a collection of practical ideas put together in one package to help all of us get through the difficult emotions humans feel. It's valuable because it works and it uses human's natural REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep processing methods.

My Newest Blog Posts

Boundaries by Neurology in Neurodiverse Relationships

Boundaries by Neurology in Neurodiverse Relationships

Once boundaries are understood as a neurologically shaped process rather than a set of rules, the next question becomes clearer: how do different brains actually experience and maintain boundaries? In neurodiverse relationships, boundary dynamics are rarely symmetrical. They emerge from distinct perceptual systems interacting in real time, each using different kinds of information to determine where self ends and other begins.

Understanding these differences does not require ranking one style as healthier than another. It requires recognizing that boundaries are formed, perceived, and repaired through different pathways depending on neurology.

Learn More About R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse™

How Non-Autistic Nervous Systems Experience Boundaries

For many non-autistic individuals, boundaries are supported by immediate social awareness. Facial expressions, body language, tone shifts, and subtle emotional cues provide constant feedback about how others are experiencing an interaction. This feedback helps regulate interpersonal distance moment by moment, often without conscious effort.

Because this awareness happens quickly and continuously, non-autistic boundaries often feel implicit. There is an internal sense of what belongs to the self and what belongs to the other, shaped by ongoing perspective-taking. This can create a flexible buffer between people—one that allows for adjustment, grace, and restraint without the need for explicit discussion.

In neurodiverse relationships, this implicit boundary system can become a source of confusion. Non-autistic individuals may assume that boundaries are mutually felt and understood, even when they are not. When their internal signals are not mirrored or responded to in expected ways, they may experience discomfort, erosion, or overextension without immediately recognizing why.

How Autistic Nervous Systems Experience Boundaries

Autistic individuals often experience boundaries through a different process. Without immediate body-based access to others’ perspectives, boundaries are more likely to be constructed through cognition, memory, and learned patterns rather than through real-time embodied feedback. Awareness of another person’s internal experience may arrive later, after reflection or explicit communication.

This does not mean that autistic individuals lack boundaries. Rather, their boundaries may be clearer internally than interpersonally. When one’s own perspective is held with intensity and consistency, it can be difficult to register where another person’s perspective diverges—especially if that divergence is communicated subtly or indirectly.

In some contexts, especially between two autistic individuals, this can result in unusually clear boundaries because communication is more direct and verbal. In other contexts, particularly neurodiverse ones, it can lead to unintentional boundary crossings—not out of disregard, but out of delayed or incomplete access to social feedback.

Where Misalignment Commonly Occurs

Boundary challenges in neurodiverse relationships often arise not because either person lacks care or respect, but because each nervous system is relying on different information to guide behavior. One person may be tracking emotional shifts in real time. The other may be tracking consistency, logic, or previously established rules. When these systems interact without shared language, misunderstandings multiply.

Common points of friction include:

assuming awareness that is not present

expecting implicit signals to be sufficient

mistaking delayed insight for indifference

interpreting accommodation as mutual agreement

Over time, these mismatches can harden into patterns. Non-autistic individuals may begin to over-accommodate, absorbing discomfort in order to preserve connection. Autistic individuals may become more entrenched in their perspective, especially if they do not receive clear feedback that boundaries have been crossed.

Why Explicit Boundaries Matter in Neurodiverse Relationships

In neurodiverse contexts, boundaries often need to be made more explicit—not because one person is failing, but because the relationship requires translation between different perceptual systems. Clear boundaries provide structure where implicit signals fall short. They offer information that some nervous systems cannot reliably infer without direct input.

Importantly, explicit boundaries support both people. They reduce the likelihood that non-autistic partners will erode their own sense of self through silent accommodation. They also give autistic partners the concrete feedback they need to understand where relational lines exist, rather than having to guess based on incomplete data.

Explicit boundaries are not a demand for conformity. They are a form of shared orientation.

Boundaries as an Ongoing Process, Not a One-Time Skill

Boundaries in neurodiverse relationships are not established once and then maintained automatically. They are renegotiated as relationships deepen, roles change, and contexts shift. What works in friendship may not work in parenting. What feels manageable early in a relationship may become unsustainable over time.

Understanding how boundaries differ by neurology allows these shifts to be approached with clarity rather than blame. It creates room for adjustment without requiring either person to abandon their natural way of perceiving the world.

In the next posts, we will explore what happens when boundary misalignment goes unaddressed—and how patterns of accommodation, withdrawal, and escalation can emerge from systems that lack shared boundary language. But before any repair is possible, boundaries must first be seen for what they are: neurologically mediated, relationally consequential, and foundational to Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics™.

Next Post In This Series: Non-Autistic Accommodation and Autistic Masking Both Lead to Escalation in Neurodiverse Relationships

Previous Post In This Series: Boundaries as a Core Element of Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics™

Learn More About R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse™

© 2023 REAL Neurodiverse

All Rights Reserved

anne@neurodiversemarriage.com

Text or Call: (617) 996-7239 (United States)