DPR

Dissociated Pain Release

A self-help technique developed by a trauma survivor

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach

Master's Clinical Psychology - Harvard University

Dissociated Pain Release

Self-Help Trauma Support

Dissociated Pain Release

Dissociated Pain Release (DPR) is a self-help technique that allows users to release emotional pain from trauma without re-experiencing it. It is based on the idea that emotional pain is stored in the mind, body, and nervous system and that the stored pain causes distress and discomfort in the present, whether the trauma was a recent event or something that happened many years ago.

There is no need for a DPR user to know where any emotional pain came from. All a user needs to know is that they are currently experiencing unwanted emotional pain and that they would like to release that pain and feel better -- quickly.

Most importantly, in DPR, emotional pains are released while the user is dissociated from them -- allowing the user to process any trauma or distress without being forced to relive the original traumatic experience.

Examples of emotional pain that can be released from the body and nervous system through DPR include rage, anger, shame, sadness, guilt, grief, loneliness, abandonment, anxiety, and fear.

Likewise, DRP allows users to release any stored sensations associated with physical pain or forms of bodily discomfort that happened in the past. DPR users can release sensations of nausea, dizziness, cold, being drugged, etc. Again, all these sensations are released without the DRP user re-experiencing the original potency of any traumatic event. Often DPR users release pain without even knowing what the original traumatic event may have been.

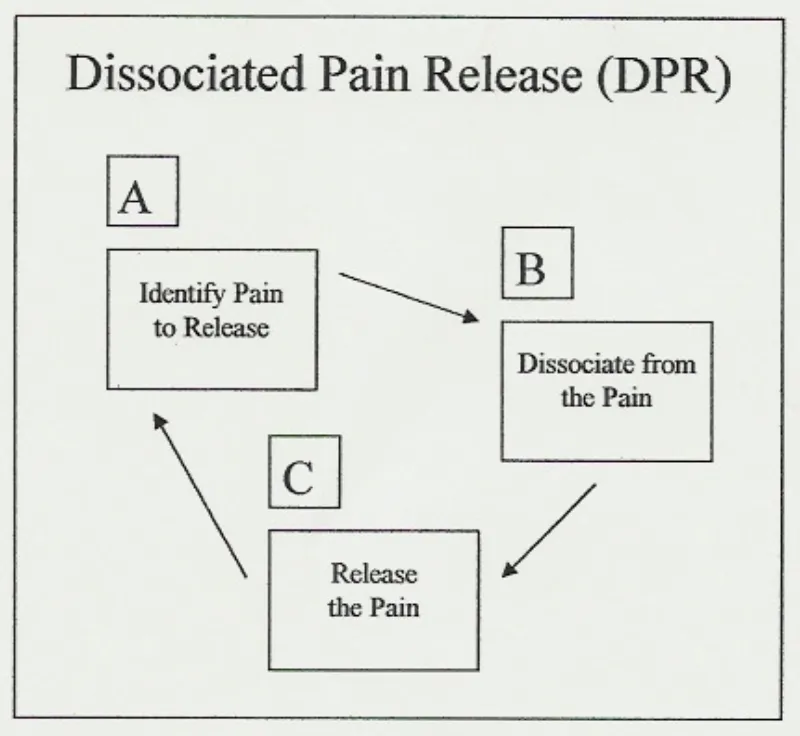

DPR has three cyclical steps: (A) identify pain to release, (B) dissociate from the pain, and (C) release the pain. Once understood, DPR is a simple, repetitive process that applies in many self-help situations. Any user employing DPR expects to complete its A-B-C cycle several times in any one self-help session. It is understood that there may be several painful emotions, different forms of physical pain and other negative bodily sensations that require release, making time and repetition necessary.

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not. It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline

Anne MacMillan, MLA

Survivor, Consultant, Coach, Educator

Master's Clinical Psychology, Harvard Univerisity

IMPORTANT

* DPR is not trauma therapy.

Anne is not a therapist and does not support individuals through trauma therapy. Anne teaches a self-help technique that individuals can apply to many situations in their everyday lives and that they have a right to use to manage any experiences they choose, traumatic or not.

It is always recommended that trauma survivors hire a licensed trauma therapists whenever possible. Call 911 in any emergency.

Feeling Suicidal?

Find a Helpline:

https://findahelpline.com/

About Me

Like many others, I grew up in a household that didn't offer me the basic protections all children need. I experienced extreme trauma as a very young child and, unfortunately, that trauma continued into my adolescence and adulthood.

I survived adolescence emotionally by focusing on studying contemporary dance, helping me process my emotions and increase my body awareness. As a young adult in my twenties, I was exposed to relaxation and meditation techniques and the idea that healing that comes naturally when we move our eyes as we dream.

In my mid-twenties, memories of traumatic events that had happened during my early childhood began to return to my consciousness. I knew about EMDR (Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy for trauma, but wasn't in a situation that allowed me consistent access to a trauma therapist.

So, I began working through my traumatic memories on my own, combining what I'd learned about the emotions I felt in my body through dancing with relaxation and visualization techniques. I added what I decided to call REM Simulation -- or Rapid Eye Movement Simulation. REM sleep is the deep dreaming sleep in which humans naturally process emotions.

The result was a self-help technique that made it possible for me to work through the terrible emotions associated with traumatic events that had occurred in my past and regain the sense of emotional stability I needed -- all without having an opportunity to get the therapeutic support I needed.

Dissociated Pain Release

I dubbed my self-help technique DPR, or Dissociated Pain Release, and decided that I didn't want it to ever become something that anyone with an advanced degree and a lot of privilege could tell people they weren't qualified to perform at home on their own.

Therapy is wonderful and everyone who has access to a therapist should take advantage of that privilege. But recovery strategies should be available to anyone anywhere. That's what DPR is about for me.

From my perspective, DPR is nothing more than a collection of practical ideas put together in one package to help all of us get through the difficult emotions humans feel. It's valuable because it works and it uses human's natural REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep processing methods.

My Newest Blog Posts

The R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse™ 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach: A Framework for Supporting Level 1 Autistic Adults and their Neurodivergent and Neurotypical Family Members

Anne MacMillan's R.E.A.L. Neurodiverse™ 10-Step Family Systems Approach supports Level 1 autistic adults and their neurodivergent and neurotypical family members as they seek to comprehend the conflict they are experiencing in their interpersonal relationships and then work towards practical solutions that will improve their quality of life. Her approach is sequential and structured yet offers the flexibility required when working with a wide spectrum of neurodivergent and neurotypical individuals having many different unique strengths and challenges.

Step 1: Accept Wholeness and Maintain a Future Orientation

MacMillan begins with a commitment to viewing both yourself and your family members as whole, capable individuals. This step emphasizes the importance of maintaining a forward-looking perspective, focusing on skill-building and actionable steps that pave the way for positive change.

Step 2: Identify and Comprehend Your Own Neurology

Comprehending one's own neurology and its associated strengths and challenges lays a foundation for understanding the self, one's own perception of the world, as well as one's own actions and experiences within a neurodiverse family system. Individuals are encouraged prioritize understanding their own neurology over their family members' neurologies and to respect and appreciate the self and one's own neurologically-based subjective experiences.

Step 3: Identify and Comprehend Your Family Members' Neurologies

The differences between Level 1 autism, attention neurodivergence (ADHD), high body empathy neurodivergence and neurotypical neurologies are not simple. Through understanding specifically how one's own neurology differs from one's family members' neurologies and what it means when one individual is of more than one neurology (e.g. autistic and attention neurodivergent), individuals can better understand their own experiences and the experiences and perspectives of their loved ones. This increased insight acts as a foundation for finding solutions, taking action and making positive change to improve relationships and quality of life. This step fosters mutual understanding and helps in recognizing the different ways each family member perceives and interacts with the social world.

Step 4: Understand Empathy Differences

MacMillan defines non-autistic body empathy and autistic emotion-sharing empathy as well as 5 distinct empathy spectrums that all individuals, regardless of neurology fall onto: 1) the empathic-emotion intensity spectrum, 2) the emotion-origin awareness spectrum, 3) the embodied simulation spectrum, 4) the interoception spectrum, and 5) the theory of mind spectrum (MacMillan, 2025). She offers quantitative assessments to support individuals as they understand where they and their loved ones fit on these five spectrums (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 5: Accept That Both Autistics and Non-Autistics Can Engage in Harmful Narcissistic Behaviors

This step challenges individuals to recognize that both non-autistics and autistics are capable of engaging in narcissistic behaviors that harm their loved ones. The notion that all individuals of any particular neurology are generally innocent or harmless only prevents individuals and families from addressing the reality that, in many cases, they are experiencing narcissistic behaviors within their neurodiverse family systems. Individuals are asked to acknowledge that excusing adult narcissistic behaviors due to individual neurology does not help families move to healthier interaction styles.

The importance of understanding psychology in terms of spectrums or dimensions rather than "types" is addressed (Coolidge and Segal, 1998; M-A. Crocq, 2013) and the history of "Narcissistic Personality Disorder" and its associated and outdated subclinical types (grandiose and vulnerable) is investigated (Miller et. al, 2017). The association between Level 1 autistic adults and all the personality disorders and, specifically, the subclinical type of vulnerable narcissism (Broglia et al., 2023) are acknowledged and addressed, even as individuals are simultaneously encouraged to discard the use of personality types and all "disorders" when working with neurodiversity.

As it is common for autistics and non-autistics to perceive the world so differently that they are unable to agree on the root cause of much of their conflict, individuals are encouraged to evaluate observable behaviors rather than incentives are cognitive mechanisms and to decide if the behaviors are narcissistic or not. Alongside a quantitive narcissistic behavior assessment, a quantitative self-respect assessment is offered to support individuals in coming to an awareness of whether or not they have a tendency to allow members of their families to behave narcissistically towards them.

Abuse should not be tolerated regardless of the neurology of the abuser and the reality that both autistics and non-autistics can be offenders or victims is acknowledged.

Step 6: Learn About Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics (NRD)

Neurodiverse relationships have distinct dynamics that differ from neurotypical relationships. MacMillan defines Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics (NRD) as including differences in psychological functioning, difficulties with relationship functioning within distinct and specific social situations that affect relationship dynamics differently (MacMillan 2025).

Psychological functioning differences include attachment differences, boundary differences, identity formation differences, and intimacy differences (MacMillan, 2025).

Relationship functioning difficulties addressed included problem solving difficulties, action impact understanding differences, and difficulties associated with passiveness, assertiveness and aggression (MacMillan, 2025).

The varying impact of neurodiversity on different social situations is addressed. Adult friendships are distinguished from family relationships, and parent-child relationships are distinguished from intimate life partnerships. The impact of autism on flirting and courtship as well as sex is acknowledged and addressed (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 7: Comprehend the Role That Trauma Plays in Your Life

Multigenerational trauma and regular intermittent trauma spikes play a significant role in most neurodiverse family systems. Residual trauma can build up in the nervous system causing difficulties over time (MacMillan, 2025). Autistics may have more difficulties recovering from trauma than non-autistics (Peterson et al., 2019). Interoceptive abilities can aid trauma relief (Brewer et al., 2016; Reinhardt et al., 2020) and the fact that many autistics likely have lower levels of interoceptive perception than autistics means that autistics require different trauma support than non-autistics (MacMillan, 2025).

A specific form of long term low grade trauma experienced experienced only by non-autistics called body empathy non-reciprocation trauma (MacMillan, 2025) is defined and addressed.

Several quantitative trauma scales are offered to support professionals and clients in better comprehending the role trauma plays in individuals' lives.

Step 8: Identify and Comprehend Individuals’ Roles and Functions in Your Neurodiverse Family System

It is common for individual members of neurodiverse family systems to take upon roles that play both individual and systemic functions within their family system. These roles tend to be more intractable than roles in neurotypical family systems because they are facilitated by the family members' neurologies. Over 15 common roles are named and defined and individuals are offered resources to support them in coming to greater awareness of the individual and systemic functions the roles are playing in their neurodiverse family systems so that they can make actionable decisions with more self-awareness and awareness of their family systems (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 9: Identify and Comprehend Interaction Cycles and Their Associated Intermittent Trauma Spikes

Individuals in neurodiverse family systems tend to cycle through periods of relative calm punctuated by intermittent trauma spikes that occur at the stress point in each cycle. These cycles are facilitated by Neurodiverse Relationship Dynamics (NRD) and, like the roles and their functions, are also fairly intractable. Four common cycles are defined and discussed allowing individuals to understand how these cycles are impacting them and offering them insight into methods they can use to slow the frequency and lessen the intensity of the resulting intermittent trauma spikes in an effort to find relief and improve quality of life (MacMillan, 2025).

Step 10: Consider Your Own Development

MacMillan's final step is reflective, encouraging individuals to consider their own personal development. MacMillan offers to complementary yet differing models of psychosocial development founded in Erik Erikson's stages of psychosocial development (1950, 1959, 1982). Her non-autistic spiral model and autistic staircase model draw on the findings of Diana Baumrind, Mihaly Csikszentimihalyi, and Jean Piaget.

Through understanding the impact of neurology on development and the differing ways autistics and non-autistics grow across the lifespan, all individuals, regardless of neurology, can work towards the psychosocial developmental milestones Erik Erikson offers and address psychological functioning differences (attachment, boundaries, identity, and intimacy (MacMillan, 2025).

By focusing on growth and self-improvement, individuals can contribute positively to their own development, their neurodiverse family dynamics and overall well-being and quality of life.

Conclusion

MacMillan's R.E.A.L. 10-Step Neurodiverse Family Systems Approach provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and improving one's own life and, whenever possible, one's neurodiverse family system. Professionals work with individuals rather than couples or family groups and emphasize that individual family members and neurodiverse family systems benefit when individuals focus on their own growth. Following these steps adds clarity and order to a situation that is often plagued by confusion, trauma and distress. The approach's educational elements support individuals in better understanding themselves and their neurodiverse family systems and its practical elements and quantitative assessments support action, decision making and positive life change.

MacMillan's 10-step approach not only addresses the challenges inherent in neurodiverse relationships but also empowers individuals to pursue the happiness and peace they deserve, regardless of neurology.

Resources for Further Exploration:

American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). DSM 5's Integrated Approach to Diagnosis and Classifications (pdf).

Brewer, R., Cook, R., & Bird, G. (2016). Alexithymia: A general deficit of interoception. The Royal Society Open Science, 3(10). doi:10.1098/rsos.150664

Broglia, E., Nisticò, V., Di Paolo, B., Faggioli, R., Bertani, A., Gambini, O., & Demartini, B. (2023). Traits of narcissistic vulnerability in adults with autism spectrum disorders without Intellectual disabilities" Autism Research. doi:10.1002/aur.3065

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Amazon link). Harper Perennial. (Republished in 2008).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (Amazon link). Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Applications of flow in human development and education (Amazon link). Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2015). The systems model of creativity (Amazon link). Springer.

Coolidge, F. L., & Segal, D. L. (1998). Evolution of personality disorder diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(5), 585-599. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00002-6

Crocq, M.-A. (2013). Milestones in the history of personality disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(2), 147-153. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.2/macrocq

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society (Amazon link). W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle (Amazon link). W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed.(Amazon link). W.W. Norton & Company. (Republished in 1993, 1994, 1998).

Kinnaird, E., Stewart, C., & Tchanturia, K. (2020). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 55, 80-98. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.004

MacMillan, A. (2025). Neurodiverse Family Systems: Theory and Practice. Available for pre-order.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in narcissism (pdf). Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 1.1-1.25. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244

Peterson, J. L., Earl, R. K., Fox, E. A., Ma, R., Haidar, G., Pepper, M., Berliner, L., Wallace, A. S., & Bernier, R. A. (2019). Trauma and autism spectrum disorder: Review, proposed treatment adaptations and future directions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 12, 529-547. doi:10.1007/s40653-019-00253-5

Reinhardt, K. M., Zerubavel, N., Young, A. S., Gallo, M., Ramakrishnan, N., Henry, A., & Zucker, N. L. (2020). A multi-method assessment of interoception among sexual assault survivors. Physiology and Behavior, 226, 113108. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113108

Rinaldi, C., Attanasio, M., Valenti, M., Mazza, M., & Keller, R. (2021). Autism spectrum disorder and personality disorders: Comorbidity and differential diagnosis". World Journal of Psychiatry, 11(12), 1366-1386. doi:10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1366

Skodol, A. E., Morey, L. C., Bender, D. S., & Oldham, J. M. (2015). The alternative DSM-5 model for personality disorders: A clinical application. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(7). doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101220

© 2023 REAL Neurodiverse

All Rights Reserved

anne@neurodiversemarriage.com

Text or Call: (617) 996-7239 (United States)